Ricardo Quaresma: Portugal’s flamboyant former star and his stand for Roma rights – BBC Sport

Known for his flamboyant range on the pitch, Quaresma is a powerful influence off it too

Known for his flamboyant range on the pitch, Quaresma is a powerful influence off it too

A mobile phone was a luxury that a young Ricardo Quaresma could not afford.

In May 2000 he was away in Israel with the Portugal Under-16s. He’d woken up feeling unwell and was desperate to get in touch with his mum back in Lisbon.

Burning up with fever, there was only one thought on his mind: how to get back home as quickly as possible.

Instead Quaresma was convinced to stay, and despite his condition he went on to play in the European Under-16 Championship final. He scored twice as Portugal beat Czech Republic 2-1 in extra-time to lift the trophy.

Those two goals would forever change his life.

Watching from the stands in Tel Aviv was Romanian manager Laszlo Boloni, who would take charge of Sporting Lisbon a year later. One of his first moves was to promote Quaresma to the senior side.

By the end of the 2001-02 season, Sporting were champions and Quaresma the breakout star of a campaign that paved the way for what was to come for him: moves to Barcelona, Inter Milan, and for a loan spell, Chelsea.

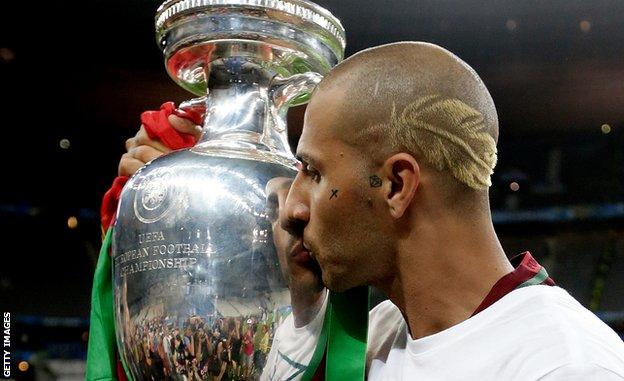

During Portugal’s victorious Euro 2016 campaign he was involved in every game. He scored the winner against Croatia in the last 16 and converted the decisive penalty against Poland in the quarter-finals.

At age 32, helping his country to its first major title was the high point of his career. But off the pitch he was making an even bigger impact.

That summer, for the first time ever, a player of Roma heritage had the entire country behind him. It led many to wonder whether a turning point had been reached.

“Can a football hero put an end to 500 years of racism?” asked Renascenca, one of Portugal’s major radio stations.

Such was the way Quaresma and his roots were embraced by fans that, before the final against France, national newspaper Diario de Noticias came up with an article stating that “our gypsy is better than theirs”. It was a reference to rival striker Andre-Pierre Gignac, another footballer of Roma origin.

After the tournament however, the mood changed once more.

“It obviously made us proud to have a member of our community excelling at the highest level, but at the same time it was a bit of a mix of emotions for us that is not easy to explain,” says Vitor Marques, founder and current vice-president of the Portuguese Roma Union.

“Unfortunately, our community is still very discriminated in Portugal. We watched an entire country give Ricardo standing ovations and sing his name, but then the following minute those very same people will refer to us all as criminals when one of our own does something wrong.

“In other words, we are not all as talented as Ricardo when he succeeds, but if a single person from our group commits a crime we’re all instantly thrown into the same bag and deemed a bunch of criminals? It shocks me every time I hear that.

“As much as Portugal doesn’t consider itself to be a racist country, there are clearly situations of racism that persist in our society.”

Quaresma himself has had to cope with them.

“I’ve never smoked, never drunk, never experimented (with drugs) nor have I ever wanted to. But there it is, because I’m Roma, I’ve got a reputation for being a lot of things in football,” he said in an interview with SIC in June 2016.

The Roma are the ethnic minority that has been around in Portugal for the longest and yet they still feel, in some way, like foreigners in their own country.

A 2016 survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rightsexternal-link found that 71% of the community had experienced discrimination within the previous five years – the highest figure among the nine countries studied.

President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa admitted in 2018 that Portugal’s strategy to fully integrate them had “failed”. Romaphobia remains deeply-rooted and has more recently become a source of political gain among the growing far-right.

“We’ve got identity cards, but very often we hear people saying: ‘Go back to your land.’ It must be the gypsyland because I don’t know where that is,” Roma activist Pimenio Ferreira told public service broadcaster RTP.

A feeling of not being wanted forms part of daily life for Portugal’s Roma population.

Research conducted by the Gulbenkian Foundationexternal-link in 2021 revealed that many considered Roma as undesirable neighbours, comparing them to alcoholics and drug addicts.

It’s not unusual to find shops, restaurants and even pharmacies making use of racist practices in an attempt to keep them away. They do that by placing ceramic frogs at their entrances as the animal is seen as a symbol of bad luck and evil, especially by elderly Roma.

One of Portugal’s biggest supermarket chains, Minipreco, had to apologise for doing this in 2019.

“We live under this idea that we are a tolerant nation, but that’s a very dangerous concept,” Marques says.

“We should embrace each other’s cultures rather than tolerate them. If we don’t change this mentality, we will never be equals.

“We’ve had the 25 April revolution that ended nearly 50 years of dictatorship and brought freedom to Portugal in 1974, but while the vast majority of citizens benefited we ended up forgotten.

“The day we are given the same conditions of access to education and work, we can say we are as Portuguese as the rest of the Portuguese, but that day has not yet arrived for us.”

An estimated 37,000 Roma live in Portugal, whose population is 10.3m

An estimated 37,000 Roma live in Portugal, whose population is 10.3m

Last year, a report from the European Committee of Social Rights of the Council of Europeexternal-link concluded that Portugal continues to violate the right to decent housing for the Roma community residing in the country.

Arguably the most illustrative example of this comes from the northern village of Torre de Moncorvo, where families were removed from tents in 2007 and placed in a deactivated prison complex, originally for only six months.

They have been waiting for a permanent solution for over a decade. Children have had to grow up in prison cells.

According to the the country’s High Commission for Migration, there were 37,000 Portuguese Roma in 2017, but the number is disputed by other sources and some estimate it to be at least three times higher.

Over recent years they have been repeatedly vilified by Andre Ventura, leader of the far-right populist Chega (Enough) party that is now the third largest force in the Portuguese parliament, having won 12 seats in January’s general elections.

A former TV football pundit, Ventura accuses Roma people of abusing welfare benefits and even proposed a specific confinement plan for them at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic because they have “a lot of difficulty in respecting the rules”.

He was publicly confronted by Quaresma, who said his “racist populism only serves to turn men against men in the name of an ambition for power that history has already proven to be a path of doom for humanity”.

In a Facebook post he added: “I have participated in several campaigns to appeal against racism, not because it looks good but because I believe that we are all the same and we all deserve the same opportunities in life.

“Eyes open friends, populism always says that it’s simple to score a goal but actually scoring a goal requires a lot of tactics and technique.”

Now 38, Quaresma is without a club since leaving Portuguese top flight side Vitoria de Guimaraes this summer. But he remains a powerful icon, and continues to apply that power in support of the Roma community.

He has recently backed the first women’s team in the country formed by Roma girls and celebrated the success of Nininho Vaz Maia, a singer who has been making waves with his performances.

“Last night, a Roma filled the Coliseu (Porto’s largest concert hall)! I’m very proud of the achievements the Roma are making in our society. Only with hard work can we defeat intolerance,” he wrote on Instagram.

Insisting he has received plenty of offers and that he isn’t ready to retire, Quaresma and his influential voice will likely remain active in football for some time to come. He plans to become a coach once he does hang up his boots.

And the fight is far from over for the Roma people of Portugal.

“For the persecution and the emptying of our culture, lifestyle and even our identities before the 1974 revolution, we deserve an apology,” Marques says.

“We were watched by the police and had to be constantly on the move because we couldn’t stay in a place for more than 24 hours. We were the most attacked community of the country.

“Other countries have apologised to their Roma people, but Portugal, no. I can only hope that one day someone will look into what we went through and what we still go through here.”