The Short, Frantic, Rags-to-Riches Life of Jack London

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/a6/68a6dfd6-19b3-48f0-99ba-90e553c8dd18/jacklondongentheweb.jpg)

An extremist, radical and searcher, Jack London was never destined to grow old. On November 22, 1916, London, author of The Call of the Wild, died at age 40. His short life was controversial and contradictory.

Born in 1876, the year of Little Bighorn and Custer’s Last Stand, the prolific writer would die in the year John T. Thompson invented the submachine gun. London’s life embodied the frenzied modernization of America between the Civil War and World War I. With his thirst for adventure, his rags-to-riches success story, and his progressive political ideas, London’s stories mirrored the passing of the American frontier and the nation’s transformation into an urban-industrial global power.

With a keen eye and an innate sense, London recognized that the country’s growing readership was ready for a different kind of writing. The style needed to be direct and robust and vivid. And he had the ace setting of the “Last Frontier” in Alaska and the Klondike—a strong draw for American readers, who were prone to creative nostalgia. Notably, London’s stories endorsed reciprocation, cooperation, adaptability and grit.

In his fictional universe, lone wolves die and abusive alpha males never win out in the end.

The 1,400-acre Jack London State Historic Park lies in the heart of Sonoma Valley wine country, some 60 miles north of San Francisco in Glen Ellen, California. Originally, the land was the site of Jack London’s Beauty Ranch, where the author earnestly pursued his interests in scientific farming and animal husbandry.

“I ride out of my beautiful ranch,” London wrote. “Between my legs is a beautiful horse. The air is wine. The grapes on a score of rolling hills are red with autumn flame. Across Sonoma Mountain wisps of sea fog are stealing. The afternoon sun smolders in the drowsy sky. I have everything to make me glad I am alive.”

The park’s varied bucolic landscape still exudes this same captivating vibe. The grounds offer 29 miles of trails, redwood groves, meadowlands, wine vineyards, stunning scenery, a museum, London’s restored cottage, ranch exhibits and the austere ruins of the writer’s Wolf House. An idyllic bounty of pristine northern California scenery is on full display. For a traveler in search of a distinctly pastoral escape fortified with a rustic dose of California cultural history, Jack London State Historic Park is pay-dirt. (It also doesn’t hurt that the park is surrounded by a myriad of the world’s premier wineries.)

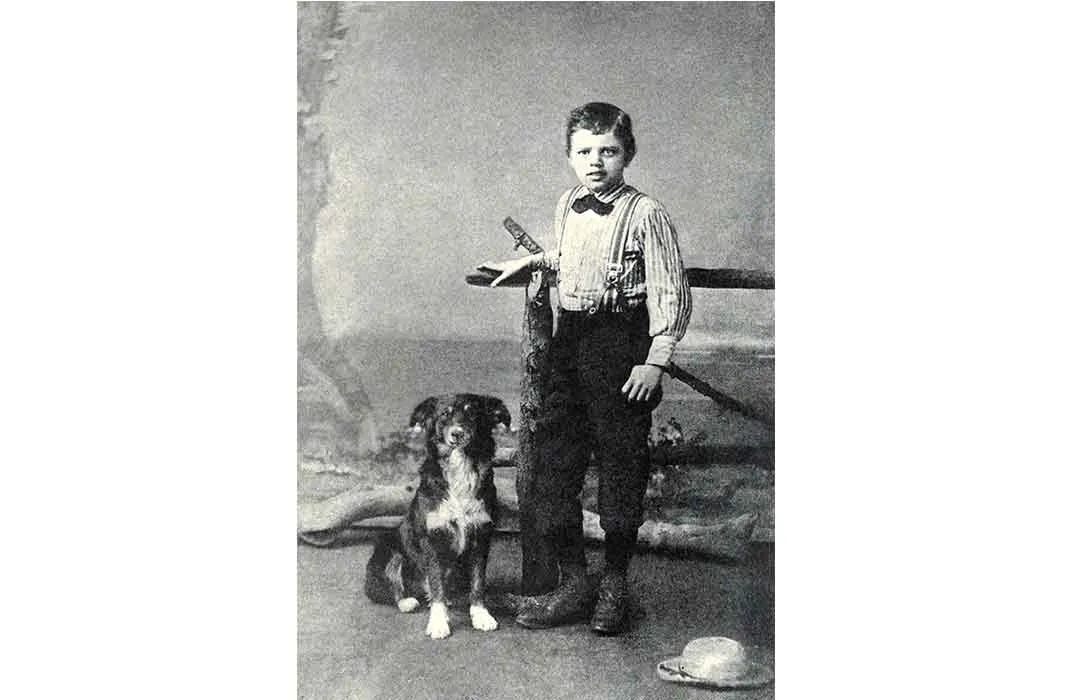

London grew up on the grungier streets of San Francisco and Oakland in a working class household. His mother was a spiritualist, who eked out a living conducting séances and teaching music. His stepfather was a disabled Civil War veteran who scraped by, working variously as a farmer, a grocer and a night watchman. (London’s probable biological father, a traveling astrologer, had abruptly exited the scene prior to the future author’s arrival.)

As a child, London labored as a farm hand, hawked newspapers, delivered ice and set up pins in a bowling alley. By the age of 14, he was making ten cents an hour as a factory worker at Hickmott’s Cannery. The scrimping and tedium of the “work-beast” life proved stifling for a tough, but imaginative kid, who had discovered the treasure trove of books in the Oakland Free Library.

Works by Herman Melville, Robert Louis Stevenson and Washington Irving fortified him for the dangerous delights of the Oakland waterfront, where he ventured at the age of 15.

Using his small sailboat, the Razzle-Dazzle, to poach oysters and sell them to local restaurants and saloons, he could make more money in a one night than he could working a full month at the cannery. Here on the seedy waterfront among an underworld of vagabonds and delinquents, he quickly fell in with a roguish crew of hard drinking sailors and wastrels. His fellow ne’er-do-wells tagged him as “The Prince of the Oyster Pirates,” and he declared that it was better “to reign among booze fighters, a prince than to toil twelve hours a day at a machine for ten cents an hour.”

The pilfering, debauchery and comradeship were totally exhilarating—at least for a while. But London wanted to see more of the world.

So he shipped out on a seal hunting expedition aboard the schooner Sophia Sutherland and voyaged across the Pacific to Japan and the Bonin Islands. He returned to San Francisco, worked in a jute mill, as a coal heaver, then took off to ride the rails and hobo across America and served time for vagrancy. All before the age of 20.

“I had been born in the working-class,” he recalled, “and I was now, at the age of eighteen, beneath the point at which I had started. I was down in the cellar of society, down in the subterranean depths of misery . . . I was in the pit, the abyss, the human cesspool, the shambles and the charnel house of our civilization. . . . I was scared into thinking.” He resolved to stop depending on his brawn, get an education, and become a “brain merchant.”

Back in California, London enrolled in high school and joined the Socialist Labor Party. By 1896, he had entered the University of California at Berkeley, where he lasted one semester before his money ran out. He then took a lackluster crack at the writing game for a few months, but bolted to the Klondike when he got the chance to join the Gold Rush in July of 1897. He spent 11 months soaking in the sublime vibe of the Northland and its unique cast of prospectors and wayfarers.

The frozen wilds provided the foreboding landscape that ignited his creative energies. “It was in the Klondike,” London said, “that I found myself. There nobody talks. Everybody thinks. There you get your perspective. I got mine.”

By 1899, he had honed his craft and major magazines began snapping up his vigorous stories. When it came to evoking elemental sensations, he was a literary maven. If you want to know what it feels like to freeze to death, read his short story, “To Build a Fire.” If you want to know what it feels like for a factory worker to devolve into a machine, read “The Apostate.” If you want to know what it feels like to have the raw ecstasy of life surging through your body, read The Call of the Wild. And if want to know what it feels like to live free or die, read “Koolau the Leper.”

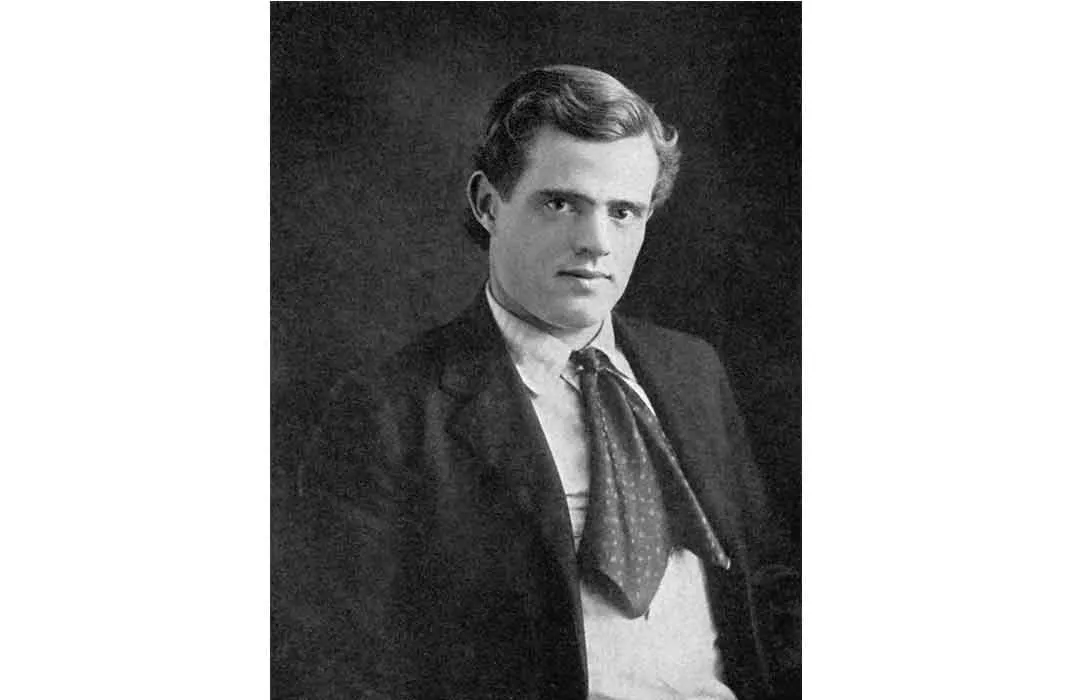

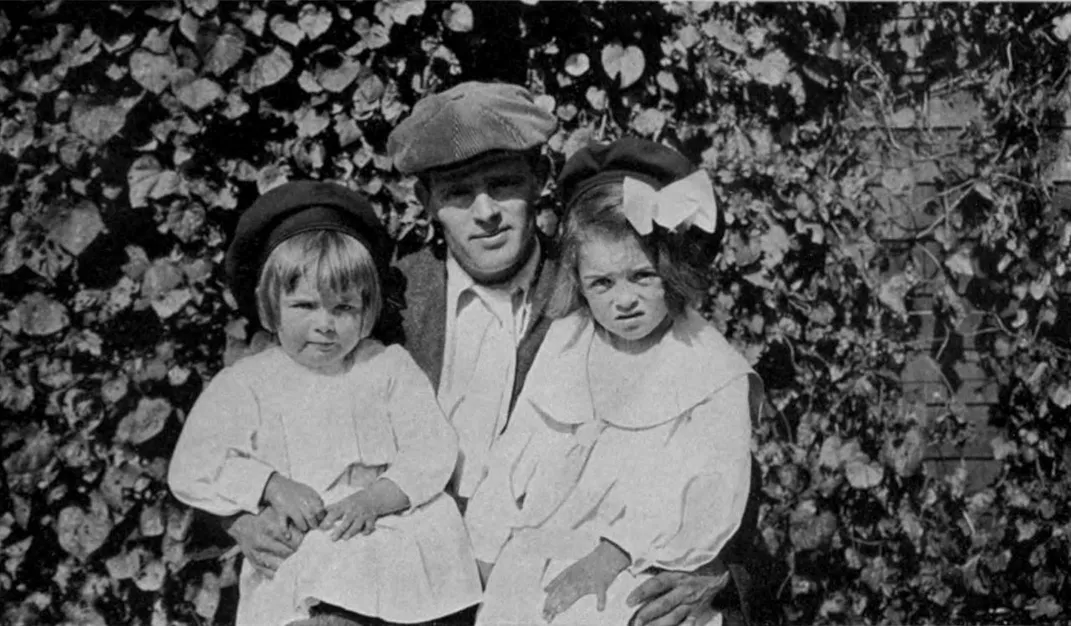

The publication of his early Klondike stories granted him a secure middle class life. In 1900, he married his former math tutor, Bess Maddern, and they had two daughters. The appearance of The Call of the Wild in 1903 made the 27-year-old author a huge celebrity. Magazines and newspapers frequently published photographs showcasing his rugged good looks that exuded an air of youthful vitality. His travels, political activism and personal exploits made ample fodder for political reporters and gossip columnists.

London was suddenly an icon of masculinity and a leading public intellectual. Still, writing remained the dominant activity of his life. Novelist E. L. Doctorow aptly described him as “a great gobbler-up of the world, physically and intellectually, the kind of writer who went to a place and wrote his dreams into it, the kind of writer who found an Idea and spun his psyche around it.”

In his stories, London simultaneously occupies opposing perspectives. At times, for instance, social Darwinism will seem to overtake his professed egalitarianism, but in another work (or later in the same one) his political idealism will reassert itself, only to be challenged again later on. London fluctuates and contradicts himself, providing a series of dialectically shifting viewpoints that resist easy resolution. He was one of the first writers to seriously, though not always successfully, confront the multiplicities unique to modernism. Race remains an acutely vexing topic in London studies. Distressingly, like other leading intellectuals of the period, his racial views were shaped by the prevailing theories of scientific racism that falsely propagated a racial hierarchy and valorized Anglo-Saxons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/59/ef59c29e-527c-406e-9fcd-b43fc073806b/jackandcharmianlondonhawaiiweb.jpg)

At the same time, he wrote many stories that were antiracist and anticolonial, and which showcased exceptionally capable non-white characters. Longtime London scholar and biographer Earle Labor describes the author’s racial views as “a bundle of contradictions,” and his inconsistences on race certainly demand close scrutiny.

An insatiable curiosity impelled London to investigate and write about a wide range of topics and issues. Much of his lesser known work remains highly readable and intellectually engaging. The Iron Heel (1908) is a pioneering dystopian novel that foresees the rise of fascism, born out of capitalism’s income inequality. The author’s most explicitly political novel, it was a crucial precursor for George Orwell’s 1984 and Sinclar Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here.

Given the economic hurly-burly of recent years, readers of The Iron Heel will readily grasp London’s depiction of a totalitarian oligarchy that makes up “nine-tenths of one per cent” of the U. S. population, owns 70 percent of the nation’s total wealth, and rules with an “Iron Heel.” His fellow socialists slammed the book when it came out because the novel’s collectivistic utopia takes 300 years to emerge—not exactly the jiffy revolution London’s radical compatriots envisioned. A political realist in this instance, he recognized how entrenched, cunning and venal the capitalist masters really were.

He also produced an exposé of the literary marketplace in his 1909 novel Martin Eden which castigates the folly of modern celebrity. Closely modelled on his own rise to stardom, the story traces the ascent of an aspiring author who, after writing his way out of the working class and achieving renown, discovers how a slick public image and marketing gimmickry trump artistic talent and aesthetic complexity in a world bent on glitz and profit. Thematically, the novel anticipates Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and it has always been something of an underground classic among writers, including Vladimir Nabokov, Jack Kerouac and Susan Sontag.

London became even more personal in his confessional 1913 memoir John Barleycorn, where he recounts the heavy significance that alcohol—personified as John Barleycorn—plays in his life. London seems aware that he abuses alcohol too frequently, but he also proclaims that he will continue to drink and dial down John Barleycorn when necessary.

For many, the book is a classic case study in denial, while others see it as an honest existential descent toward the pith of self-awareness. The problem with John Barleycorn for London (and the rest of us) is that he both giveth and taketh away. Drink paves the way for comradery, offers an antidote to life’s monotony, and enhances the “purple passages” of exalted being. But the price is debility, dependence, and a nihilistic despondency he calls the “white logic.” Remarkably unguarded and frank, London discloses how the pervasive availably of drink creates a culture of addiction.

As a journalist, London’s articles on politics, sports and war frequently appeared in major newspapers. A skilled documentary photographer and photojournalist, he took thousands of pictures over the years from the slums of London’s East side to the islands of the South Pacific.

In 1904, he traveled as war correspondent to Korea to report on the Russo-Japanese War but was threatened with a court marital for punching out a Japanese officer’s thieving stable groom. President Theodore Roosevelt had to intervene to secure his release. The next year, London purchased the first piece of land in Glen Ellen, California, which would eventually become the 1,400-acre “Beauty Ranch.” He also embarked on a nation-wide socialist lecture tour that same year.

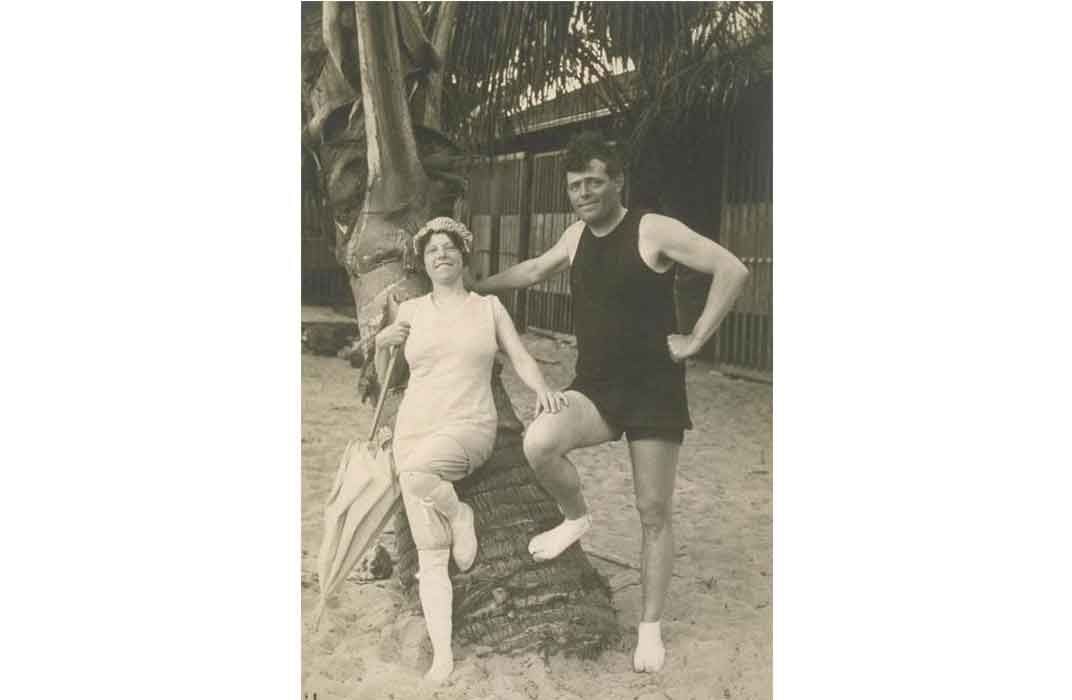

After his marriage collapsed in 1904, London married Charmian Kittrege, the epitome of the progressive “New Woman”—gregarious, athletic and independent—and with whom he had an affair during his first marriage. They would remain together until London’s death.

Following the publication of two more immensely successful novels that would became classics, The Sea-Wolf and White Fang, London began designing his own 45-foot sailboat, the Snark, and in 1907 he set sail to Hawaii and the South Seas with his wife and a small crew. A host of tropical ailments would land him in an Australian hospital, and he was forced to end the voyage the following December. Though he projected enormous personal energy and charisma, London had frequent health issues over the years, and his hard drinking, chain smoking and a bad diet only worsened matters.

London was well ahead in the real estate game in 1905 when he began buying up what was then exhausted farmland around Glen Ellen. His intention was to restore the land by using innovative farming methods such as terracing and organic fertilizers. Today, docents lead tours showcasing London’s progressive ranching and sustainable agricultural practices.

The author’s tidy ranch cottage has been painstakingly restored, and London’s workspace, writing desk, and much of the home’s original furniture, art and accoutrements are on display. Visitors can learn much about London’s action-packed life and agrarian vision. “I see my farm,” he declared, “in terms of the world and the world in terms of my farm.”

But London took time out from his farm for extended excursions. In 1911, he and his wife drove a four-horse wagon on 1,500-mile trip through Oregon, and in 1912 they sailed from Baltimore around Cape Horn to Seattle as passengers aboard the square-rigged sailing bark Dirigo.

The next year London underwent an appendectomy, and doctors discovered his seriously diseased kidneys. Weeks later, disaster hit when the London’s 15,000 square-foot ranch home, dubbed Wolf House, burned down shortly before its construction was completed. Built out of native volcanic rock and unstripped redwoods, it was to be the rustic capstone of Beauty Ranch and architectural avatar Jack London himself. He was devastated over the fire but vowed to rebuild. He would never get the chance.

Late photographs show London as drawn and noticeably puffy—the effects of his failing kidneys. Despite his deteriorating health, he remained productive, penning innovative fiction like his 1913 The Valley of the Moon, his 1915 “back to the land” novel, The Star Rover, a prison novel about astral projection, as well as a medley of distinctive stories set in Hawaii and the South Seas.

He also remained politically engaged. “If, just by wishing I could change America and Americans in one way,” London wrote in a 1914 letter, “I would change the economic organization of America so that true equality of opportunity would obtain; and service, instead of profits, would be the idea, the ideal and the ambition animating every citizen.”

This remark is probably the most succinct expression of London’s sensible brand of political idealism.

In the last two years of his life, he endured bouts of dysentery, gastric disorders and rheumatism. He and his wife made two extended recuperative trips to Hawaii, but London died on Beauty Ranch on November 22, 1916 of uremic poisoning and a probable stroke. In 18 years, he had written 50 books, 20 of them novels.

The stony ruins of Wolf House still stand today with eerie dignity on the grounds of the Jack London State Historic Park. They are there and will remain simply because Jack London lived.

A scenic six-mile trail leads to the top of Sonoma Mountain and visitors can also explore trails on horseback or by bike. The park has a museum in “The House of Happy Walls,” where displays of London’s books along with paraphernalia unique to the author’s adventures and writing career help reveal his life story. Particularly fascinating are the artifacts London and his second wife, Charmain, collected on their travels in the South Pacific, which include an array of masks, spears and carvings.

A major attraction are the ruins of London’s Wolf House, which is a short hike from the museum. Wolf House was London’s dream home, a rugged Arts and Crafts style residence constructed of native volcanic rock and unstriped redwood timbers.

In 1963, the Wolf House site was designated a National Landmark, and its craggy remains emit a special energy—simultaneously ghostly and restorative. Perhaps this eeriness has something to do with the fact that London’s cremated remains lie a few hundred yards away from the ruins under a rock rejected as too large by the builders.

London wrote of his Beauty Ranch, “All I wanted was a quiet place in the country to write and loaf in, and get out of nature that something which we all need, only the most of us don’t know it.” For the hiker, nature lover, reader, historian and environmentalist—for everyone—“that something” endures at the Jack London State Historic Park. It’s worth the drive.

Kenneth K. Brandt is a professor of English at the Savannah College of Art and Design and the executive coordinator of the Jack London Society.

Editor’s Note, December 14, 2016: This story has been updated to include new information about visiting and touring Jack London State Historic Park in Glen Ellen, California.