The Goalie Who Faced Pablo Escobar’s Empire

This article originally appeared in the June 1994 issue of Esquire. It contains outdated and potentially offensive descriptions of race, nationality, and class. You can find every Esquire story ever published at Esquire Classic.

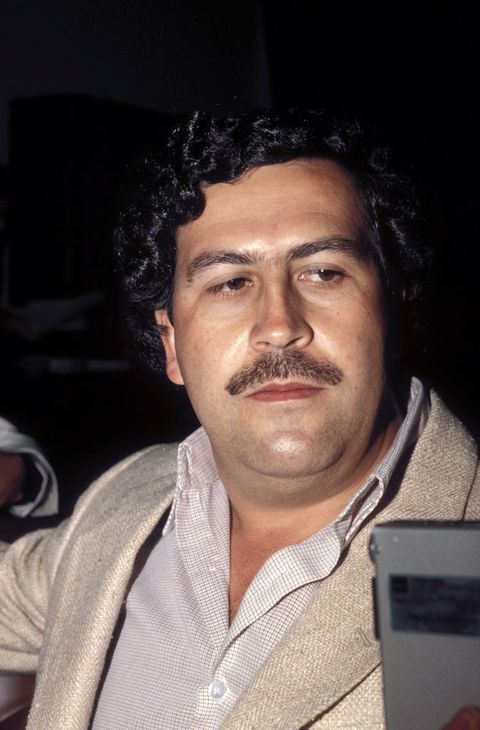

The rival Columbian drug lords Pablo Escobar and Carlos Molina Yepes had one thing in common besides their enthusiasm for the marketing possibilities of cocaine: a love for the game of soccer. Before he went underground, Escobar was known in Medellín merely as a local politician, a member of parliament who was more at home on the terraces of the city’s stadiums, appraising the talents of players who had grown up in the roughneck neighborhoods nearby. So notorious was his passion for fútbol that even after he vanished, there were Elvis-like sightings of Escobar in the stadiums of Medellín. His investment in the club Atlético Nacional de Medellín, through his testaferros, his front men, was said to be vast. For the local soccer team was one of his toys, like his imported giraffes and rhino, and it was said that many star players were enriched by his favors.

Molina, like Escobar, haunted the terraces. He, too, operated behind testaferros as an investor in Nacional. As such, he knew the players intimately—what their moves were on the field and who their associates were off it. This was knowledge that would prove invaluable when Molina’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Claudia, was kidnapped while out walking in Medellín one afternoon last spring. Within days, the suspicion grew that Molina’s fellow soccer fan and former business partner, Escobar himself, had engineered the abduction.

The kingpin of a declining cartel, Escobar desperately needed cash, and since he and Molina were now confirmed enemies, he had no scruples about taking his antagonist’s daughter hostage. It was the endgame for Escobar. He was on the run after his fabled escape in July of ’92 from the mountaintop prison above Medellín, where he had lived like drug royalty, surrounded by women, good food, and soccer videos, guarded by his own men. Now he could no longer access his own bank accounts, and when he turned to his former associates for a “loan” of a million dollars, they refused him. Escobar rewarded this lack of fidelity by having them murdered. As a last resort, he decided to raise money the old-fashioned way: He would steal it by kidnapping and ransoming the family members of his underworld rivals.

Original Esquire magazine spread.

Esquire

In his distress over his daughter’s abduction, Molina importuned not the police, not the government, but the flamboyant, freewheeling goalkeeper of the national soccer team who had grown up poor in Medellín. His name was René Higuita. As a result of both his background and his growing notoriety as the wildest world-class goalie around, Higuita enjoyed access to all levels of Medellin society, from the politicos to the drug dealers, who, in fact, were often one and the same. Unfortunately, his association with Molina has now come close to destroying his career, in the process revealing the nexus in Colombia between soccer and the drug cartels. The sad truth is that if Higuita, the man they call el Loco, had been as nimble navigating the law as he was the soccer field, perhaps he might have spent more time last year guarding a goal than being guarded in a Colombian jail.

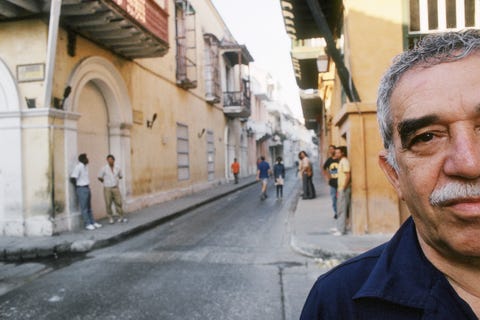

This summer, in American stadiums normally reserved for steroid-crazed linebackers and tobacco-slobbering outfielders, the Colombian national soccer team will be on a dual mission: to win the World Cup and to eradicate the country’s image as the world’s largest cocaine theme park. According to Colombia’s Nobel prize-winning author, Gabriel García Márquez, the team has become an instrument of national redemption. “All the bad publicity will end when we make goals.”

With Higuita’s brazen, improvisational forays upfield, he has not only revolutionized his position but also come to embody the free-flowing grace of Colombian soccer. He is a player whom Americans, no matter how unschooled in fútbol, would have embraced, just as they do the “I’ll do it my way” antics of Charles Barkley. It is especially poignant, then, that when his teammates take the field in Pasadena on June 22 against the United States, Higuita may find himself back in Medellín, watching it all unfold without him.

When Higuita showed up at Molina’s house shortly thereafter, the drug boss said to him, “The life of my daughter is in your hands. I need your help.

That’s because on the road to the World Cup, René Higuita became entrapped in the internecine disputes splintering the Colombian cartels. This has made him a target of a government taking aim at drug-induced corruption.

Higuita’s trials began with a simple phone call last spring. The message from the drug lord Carlos Molina arrived with gangster authority: “Come to my house. I need to see you. I will send a car.”

Pablo Escobar, 1988.

Eric VANDEVILLE

//

Getty Images

When Higuita showed up at Molina’s house shortly thereafter, the drug boss said to him, “The life of my daughter is in your hands. I need your help.”

What could Higuita say? What could anybody say? To begin with, Molina was an investor in Atlético Nacional, the club Higuita starred on. But more ominously, Molina was also a member of the Medellín cartel and a prime suspect in an assassination. Wouldn’t Higuita have known that Escobar was probably behind the abduction of Molina’s daughter? Wouldn’t he have realized that to become involved in this kidnapping could not only wreck his career but get him in trouble with the authorities and land him in jail? On the other hand, might he not have foreseen that even going to jail could be a safer alternative than stumbling into the middle of a vicious fight between two former cartel associates?

“Higuita is like a child, but he is not stupid. When a Medellin drug baron says, ‘Do me a favor,’ it is impossible to say no. The consequences of refusal are clear.”

“I need your help,” Molina insisted that day, a request that straddled the line between entreaty and command. What Higuita did after this second plea is the subject of much rancorous dispute. There’s no denying that he was damned if he helped and damned—or dead—if he didn’t, but there are degrees of involvement in such cases that are telling. I went to Colombia to find the legendary Higuita and to understand whether he was a sweet-tempered dupe of the drug lords, a fame-addled Good Samaritan, or a low-life superstar who thought he was above the law. Everyone in Colombia, it seemed, had an opinion—from the president to the literati to the paisas, as the people of Medellín are known. Of course, it should not have surprised me that my fellow journalists would also be quick to proffer their views. “Look,” says Hector Rincón, a Medellín newspaperman, “Higuita is like a child, but he is not stupid. When a Medellin drug baron says, ‘Do me a favor,’ it is impossible to say no. The consequences of refusal are clear.”

Higuita was always known to be a generous soul, hardly inclined to refuse anyone’s request, though in this case his natural generosity was no doubt shaded by fear. His entire life on and off the field had trained him to calculate the risks inherent in every raid on his territory. He’d been born twenty-seven years earlier in the barrio of Castilla, a vast patchwork of simple brick-block houses spread over a mountainside in north Medellín. He had no relationship with his mother, and his father had deserted the home, leaving René in the care of his grandmother. On a dusty, grassless soccer field called Maracaná, under lights that Pablo Escobar had installed, Higuita found a refuge from his difficulties. During that same period he no doubt first heard of the legend of el Patrón, since the drug dealer’s philanthropy had made the name Escobar magic in Castilla. Higuita’s first professional contract came at the age of seventeen. The team that signed him was Millonarios, a Bogotá club that would soon be taken over by Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, known as el Mexicano, who would be killed in a joint DEA-Colombian-police helicopter raid in 1989.

René Higuita, photographed in the mid-’90s.

DANIEL LUNA

//

Getty Images

In 1987 Francisco Maturana, the Colombian national coach, discovered in Higuita the perfect goalkeeper. As a youth, René had been trained as a forward. This fostered in him the predatory nature of a goal scorer, which, along with his lightning reactions and wonderful agility, made for a bold new breed of goalkeeper. Higuita thrilled the fans with his madcap dashes out of the goal area, frequently dribbling half the length of the field as if he were still a freelancing attacker, not a goalie on holiday. Galvanized by Higuita’s uninhibited style, Colombia enjoyed a string of great triumphs, including a stunning upset of the Maradona-led Argentine juggernaut, fresh from its 1986 World Cup championship. Of course, sometimes this brashness could prove catastrophic, most memorably in the 1990 World Cup, when Higuita was caught dribbling blithely near midfield by Cameroon’s Roger Milla, one of the oldest players in the tournament that year. With the Colombian television commentator screaming hysterically on the broadcast, “No, Higuita! No, Higuita! No, Higuita!” Milla swiped the ball, loped goalward, and coolly scored. The shot eliminated Colombia from the Cup and transformed Higuita into a national disgrace, reinforcing the nickname that he had already acquired, el Loco.

The players lived and competed in a shadowland where they were virtual slaves to the owners of their clubs. Buying soccer players was a good way for corrupt owners to launder drug money.

That world-class gaffe tarnishes his reputation to this day, but not nearly so much as does his association with the Colombian underworld. Such ties, however, were practically unavoidable. The players lived and competed in a shadowland where they were virtual slaves to the owners of their clubs. Buying soccer players was a good way for corrupt owners to launder drug money. Management may have been sleazy, but it wasn’t necessarily miserly. When the athletes performed well, they were rewarded with substantial bonuses from often anonymous benefactors. Indeed, after Escobar escaped from his mountaintop prison, bonus checks to Higuita and other star players were found in his “cell.”

Through the 1980s, the drug cartels competed not only for market share but for victory on the soccer field as well. For four successive years, until 1993, Medellín and Cali battled each other for the national championship. The stakes were high. There were rumors that referees were routinely intimidated and bribed, sometimes receiving as much as $180,000 to influence the outcome of a game. In 1989 a linesman was murdered after he disallowed a goal in what was a scoreless tie involving teams representing Medellín and Cali. The murder was tied to a $750,000 bet that was placed on the game in Medellín. In February 1993 the body of Higuita’s teammate Omar Darío Cañas, a promising striker, was found bound and shot at close range. Police believed Cañas was the victim of a group known as los Pepes (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar), which flourished during Escobar’s final days and received support from the Cali cartel.

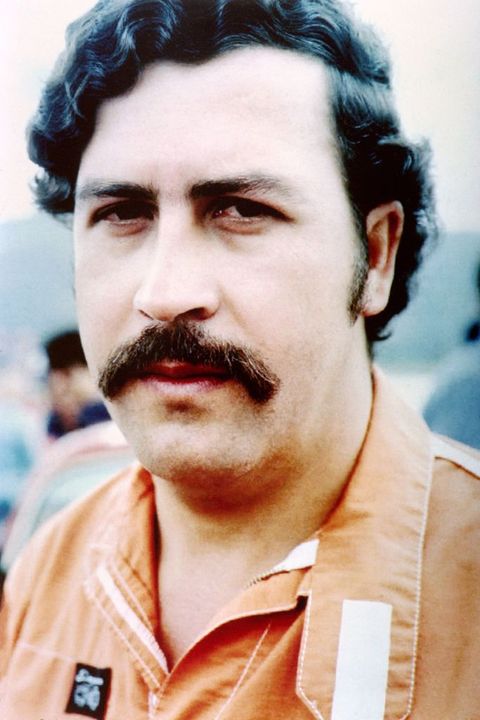

Escobar photographed in prison in the 1990s.

–

//

Getty Images

In fact, at its peak, Escobar’s influence over Colombian soccer was said to extend far beyond his hometown. When the electrifying forward of the national team, Faustino “el Tino” Asprilla, then playing for Atlético Nacional, was offered a lucrative contract to play for Parma in Italy, Escobar’s approval of the deal was considered a prerequisite. In these shady climes, Higuita flourished. He enjoyed his first visit with Escobar in 1987, when Higuita was twenty-one. He had been spending the weekend at his in-laws’ finca when the call came that el Patrón, then in hiding, wished to see him. Invitations like this were hard to refuse. According to Higuita, the two men talked mainly about soccer, though at one point Higuita suggested to Escobar, “Why don’t you go to the authorities? It would be good for the country.” Their next meeting came in 1991, after Escobar had apparently taken Higuita’s advice and ended up in a jail high above Medellín, a place called la Catedral. By his own account, Higuita thanked Escobar for giving himself up. Things would be better for Colombia now. Why had Escobar wanted to see him? “He was like a lot of other Colombians who want to meet me,” Higuita replied.

This second meeting was devastating to Higuita’s reputation, leaving the impression that he and Escobar were close friends, perhaps even engaged in some sinister business together. For this he was vilified by the press, which had been prodding him to say something negative about Escobar.

“René Higuita does everything from the heart,” he would tell me on the day I finally tracked him down at his home in Poblado, a section of Medellín. “I can’t say anything bad about anybody, because that’s not who I am. Why should I say something that everybody knows anyway? Why didn’t others who had more authority about drug trafficking speak up?”

Higuita lives in a chalet nestled among tall brick apartment houses whose residents have a privileged view of his private affairs, especially those taking place around the pool, which is decorated with cages of rare Amazonian birds, including an endangered prow-billed toucan.

Higuita, photographed before a match in 1993.

David Cannon

//

Getty Images

When he came down the stairs to greet me that afternoon, Higuita was more robust than I had imagined. He had been freed from prison only three weeks earlier, after having endured a seven-month jail term that had culminated in a well-publicized hunger strike that helped secure his release.

He seemed the very picture of ease, his trademark hair—jet-black and curly—cascading to his shoulders, and I understood immediately why he had cared enough to sue the prison when his jailers picked up the scissors. “His hair,” his lawyer had announced, “is essential to his personality, his performance, and his image.” His face is dark and Indian, a mixture of the Andes and Africa. He has high cheekbones, small eyes, a Zapata mustache, and a wonderful, childlike smile that is just as much a part of his power as his hair. He wore a Florida Marlins T-shirt.

He had been on television that day, suction cups stuck to his beefy chest and an oxygen mask covering his broad face as he ran on a treadmill. Below him, eager technicians watched the numbers and prepared to render their scientific judgment as to just how out of shape Higuita was after his time in prison. When the tests were over, he was pronounced to be in sound physical health. His training could commence in earnest. Three months remained for Higuita to prove himself once again to be, if not the best, certainly the most entertaining goalkeeper in Colombia and the world. His aim was to rejoin the national team, to come to the United States and reclaim his greatness.

Higuita during a face-off with England in 1995.

Ross Kinnaird – EMPICS

//

Getty Images

As we began to talk, a tremendous explosion rocked the ground nearby. I blanched. “Don’t worry,” Higuita said. “They’re building an apartment, and that’s just dynamite.

“You see how I live,” he went on. “I live simply. I try hard in games. I try to help my country and bring peace to my people. I have no bodyguards. Sometimes people say, You must be crazy not to have bodyguards like the others. But they’re just trying to show off how important they are. The difference is, I don’t owe anything to anybody.”

We could not talk any further just now, he announced, because he had to get back to the stadium for afternoon training. So we piled into his green Toyota Jeep and headed down the hill. Higuita has that celebrity trait of knowing many eyes are on him without seeming to notice. When we stopped for lights, the locals gave him the thumbs-up and shouted, “Hey, Higuita! Hey, René! Viva Higuita!” He is a cause as well as a celebrity now, both hero and victim. Once, at a light, a man crossing the street shouted out so loudly that Higuita could not ignore it. “Hey, Higuita! Going to the World Cup!” It is the standard cheer.

Higuita smiled at the exuberance. “Con la ayuda de Dios,” he said. With God’s help.

The afternoon session was light—slow laps around the stadium and weight-training in the gym. After Higuita emerged from the showers, we made our way back to his Jeep. On the street, children seemed to materialize from the pavement. They pulled on his sleeve and pushed Chiclets in his face. “René, René,” they called softly, as if a greeting or nod was enough. When a scruffy man in rags joined their number, Higuita slipped him two hundred pesos with a practiced sleight of hand.

We took off with a start. More than a block away, near a low-slung stucco building, he abruptly slowed to a stop and parked. This was the spot, Higuita announced in a reverential tone, where he had received the kidnapped girl. “This is where my martyrdom, my calvary, began,” he said. “I went to jail because I tried to save a teenage girl.”

Even in the midst of a hostage transfer, the street children discovered Higuita, who casually began to sign autographs while they waited for the kidnapped girl.

And so he would start his story at its heroic climax. Molina had needed his help and so Higuita had obliged. What else could a son of Medellín have done? Molina gave the soccer star a briefcase packed with the equivalent of $300,000 in pesos. Higuita took the briefcase home, where it sat for the next month. Every day Molina phoned, but there was no word from the kidnappers. Higuita was growing quite nervous, he told me, when the call finally came.

Soon after, two men showed up at his house, and with Higuita, they drove to downtown Medellín, near a college named Pontificia Bolivariana. “This very place,” Higuita said. He handed over the ransom money to one of the men, who disappeared into the neighborhood. The other man stayed with Higuita.

This seemed ominous, but the man reassured the goalkeeper: “I’m staying as a guarantee that the girl will be delivered.” Even in the midst of a hostage transfer, the street children discovered Higuita, who casually began to sign autographs while they waited for the kidnapped girl. It was while he was busy with the children, Higuita said, that the man startled the star out of his signing. “Here she comes,” the man said excitedly, gesturing behind them.

Higuita swung around and spotted a mature woman walking toward them. “No, that can’t be her,” he said, thinking of Molina’s fifteen-year-old daughter. “That’s not her.” When he turned back around, there, in the midst of the street urchins, was Molina’s daughter. Higuita’s attention had obviously been diverted so that he would not see how the girl got there.

In the days afterward, the goalkeeper made no secret of his glamorous role as the savior of Claudia Molina. Indeed, he boasted to the press about it. “It was a mission from God,” he said. “It was a very beautiful thing. I did it as a blessing, because God gave me the chance to make a family happy. It is not often in life that you get such a chance.”

A screen-grab of Escobar from the 1980s.

TONY COMITI

//

Getty Images

The Colombian attorney general’s office took note of this braggadocio. By his own admission, Higuita had been an accessory to a kidnapping, exactly the sort of crime the government was especially eager to stamp out. And he had failed to report that crime to the authorities. Indeed, as the investigation got under way, another accusation against Higuita surfaced. Carlos Molina had been so grateful to el Loco that he had pressed $64,000 on him as a gesture of appreciation.

“Brother, we have no other way to thank you,” Molina had said. “With all our heart, we want you to have this.” At first, Higuita said, he refused the gift. But Molina insisted, and his daughter’s savior finally gave in. “They practically made me take it,” Higuita says in his defense. But by doing so, he stood accused of the most damaging count against him: He had enriched himself by his role in a kidnapping.

Not even the charming people’s champion could scamper away from what came next. In June of 1993, without being indicted or tried, René Higuita, on the very suspicion of violating Colombia’s stiff anti-kidnapping law, was trundled off to a Bogotá jail, where he would spend the next seven months cut off from the building excitement that accompanied the nation’s emergence as a favorite for the World Cup.

Higuita pauses before getting into the car, taking a deep breath and seeming to savor his release from confinement. After all, his ordeal may not be behind him. If he is tried and convicted, he stands to spend another two years in prison. “And my only crime,” he pleads again in a now-familiar refrain, “is that I tried to save a little girl.”

I needed a wider perspective, a better way of assessing Higuita’s place in Colombian society. So I flew up to Cartagena to see the most famous Colombian of all: the author Gabriel García Márquez. For thirty-five years, García Márquez lived in Mexico City and Spain and Paris. He traveled extensively and started a filmmaking institute in Cuba. But a few years ago, to the pride of his countrymen, he returned home, resuming an active role in Colombia.

Gabriel García Márquez, 1990.

Ulf Andersen

//

Getty Images

Although I knew him to be a great fancier of bullfights—he was giving up one to see me that Sunday afternoon—I didn’t expect he would be such an avid soccer fan. But I was sure that Higuita’s dilemma would interest him, if only for the connection to Colombia’s curse of drug terrorism. García Márquez had rocked Colombia a few months before by arguing for the legalization of drugs.

He picked me up at my guesthouse and we drove to an elegant hotel, settled down by the pool, ordered drinks, and began to talk about Higuita, his country, and the World Cup. He wanted to establish at the outset that Colombia would win the Cup. “If I say it, then my countrymen will begin to believe it more,” he said grandly.

To Colombia, at this stage in its history and development, no greater force for national unity than the World Cup team existed, García Márquez professed. Only the music of the country matched soccer’s influence. Soccer was, he said, “the cultural strength of the country. We were always an elegant team. We learned from Brazil and Argentina, but we did not know how to score goals. Now we know.” Was Higuita a victim? I asked. “The victim is the person who was kidnapped,” he snapped. “Higuita is a great goalkeeper, one of the best in the world, but there must always be justice, even for great goalkeepers.” What if Higuita was free to star in the World Cup? Did Garcia Márquez share the wide concerns of many high officials that this would be a disaster for Colombia? “If Higuita is called to the team,” Miguel Silva Pinzón, the chief of staff to President Cesar Gaviria Trujillo, had told me earlier, “it will be considered a narco team. The American press will seize upon it, and they would have a lot to go on. And I am concerned not only about international cosmetics. It would be very bad internally. Higuita crossed the line and became an apologist for Escobar.”

“Higuita crossed the line and became an apologist for Escobar.”

“Just because he is a great goalkeeper does not help him win the criminal case,” García Márquez replied. “Look, when the Colombian team returned from Buenos Aires after the 5–0 victory [in the World Cup qualifying match against Argentina], the players asked the president to free Higuita. That was an abuse. They should not have done that. The process is working as it should. We want to be soccer champions but also champions of justice.”

That was his technical answer to the criminal case of René Higuita. But in the wider, social context, yes, he saw Higuita as a victim of the social conditions. A humble man, like all the Colombian players from very poor backgrounds, el Loco was caught up in the culture of Medellín, where Pablo Escobar reigned supreme and controlled the Medellín club for which Higuita played. They socialized together, and Higuita benefited. Suddenly, Escobar lost his grip, was pursued, and killed. And so Medellín’s other most famous person lost his patrón and became a victim of historical transition.

Garcia Marquez, 1991

Ulf Andersen

//

Getty Images

“In that sense, half the country are Higuitas,” Garcia Márquez said. “A central quality of the Colombian is that he always wants just a little more than he has, and he will get it, one way or another. The social conditions here don’t always allow him to get what he wants legally. And this sometimes leads to bad methods. If you apply that simple principle, you will understand everything about Colombia. When we went to Argentina, we wanted not to lose. Then we beat Argentina. Now we want the World Cup.”

García Márquez then surprised me with an admission: “It is true that the success of soccer in this country is partly due to the investment in the teams by drug traffickers. But that has nothing to do with the high skill of the players. If the players are not good, all the drug money in the world means nothing.”

“But don’t you see how dangerous that is for the team’s image in the World Cup?” I asked.

“Colombia will be judged by the goals it scores,” he snapped. “I am one of the best-selling and most-studied authors in the United States. Nobody says, ‘I won’t buy one of his books because he comes from a drug-trafficking country.’”

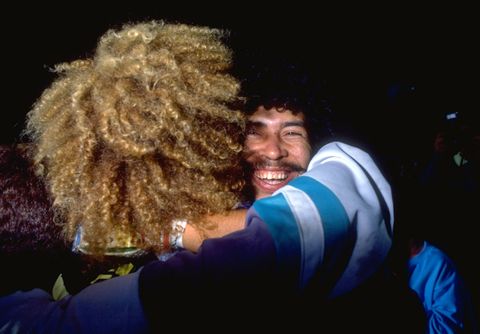

Higuita with Carlos Valderrama of Colombia, 1989

Ben Radford

//

Getty Images

We sat by the pool, the dying strains of a salsa band drifting across the water, “Gabo” draped in crumpled white cotton and white shoes. His presence spread in whispers and glances and gestures, for his celebrity is Hemingwayesque. “I was away for thirty-five years, but I never left for good,” he said wistfully.

The hour was getting late, and I was eager to make the last flight back to Bogotá. García Márquez, too, was growing restless. It was ironic that he was making a case for his return to Colombia at the very moment when Higuita, the subject of our genteel talk, was agitating for the chance to leave the country to play in the World Cup. This disjunction lent a special poignance to the parable García Márquez proceeded to make out of the ceremony in which he was awarded the Nobel prize.

“When I won the Nobel prize,” he said, “I called the president of Colombia, who was then Belisario Betancur. I told him to please not leave me alone in Sweden for this event. And so he filled a jumbo jet full of dancers and musicians from all over the country, and they took over the streets of Stockholm. The most important event was the dinner with the king and queen. It began with a lovely choir of children. Then there were speeches. And afterward, suddenly, drums rolled, the doors opened, and through them, in their colorful costumes, came the dancers and musicians. I was paralyzed. This will be a disaster or an apotheosis, I thought.

Valderama, early ’90s

RENARD eric

//

Getty Images

“But then the young queen began to sway her shoulders to the cumbia. She said she had learned it in Brazil. Before long the king was asking if the dancers could not teach him the cumbia. When it was all over, he turned to me and said, ‘Colombia has taught us how to celebrate the Nobel prize.’”

He paused. “If you want it for the World Cup, I will send these dancers and musicians to take over the streets of America.” Dancers and musicians, yes, why not? But what about Higuita? Where will he be when his teammates go north to win a championship and redeem a country?

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.