Edogawa Ranpo: A Famous Japanese Author of Mystery Fiction | YABAI – The Modern, Vibrant Face of Japan

Time and time again, there are people who are born to touch the lives of other people through their chosen profession or craft. There are many professions that influence the hearts and minds of people and one of them is a writer. Writing stories that make people think about the world and its inhabitants is not such an easy feat, may it be fiction or nonfiction. One such writer that had achieved this hailed from Japan. He was known as Edogawa Ranpo.

The Early Life of Edogawa Ranpo

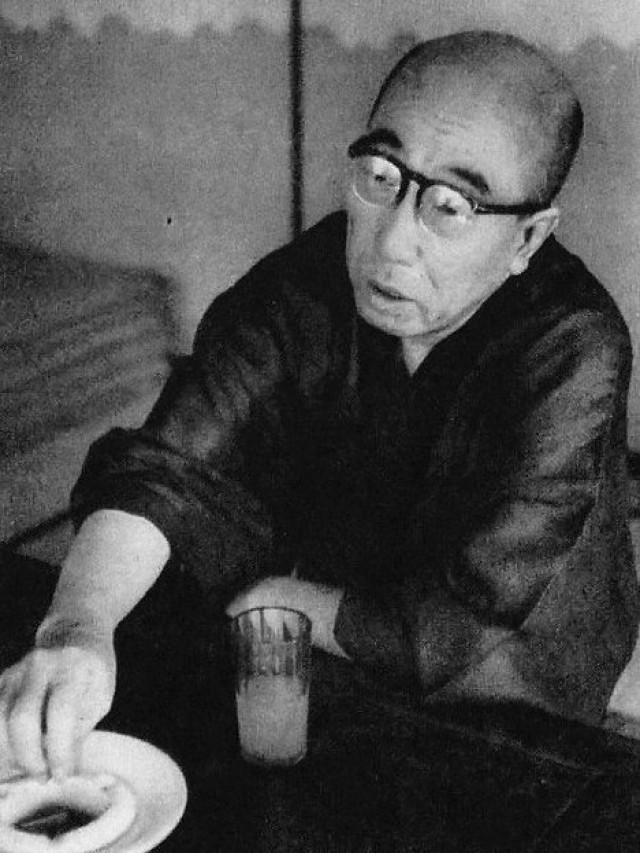

By UnknownUnknown author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

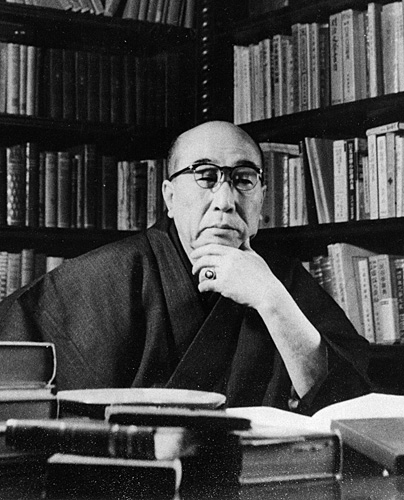

By UnknownUnknown author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Born on the 21st of October in the year 1894, Taro Hirai was a well-known Japanese writer. In the literary scene, he was better known by his pen name, Edogawa Ranpo. Throughout his career, his works played a huge role in developing mystery fiction in Japan. Several of his novels include Kogoro Akechi, a character who was a detective. In later books, Akechi became the leader of the Shonen Tantei Dan, which translated to “Boy Detectives Club,” a group of boy detectives.

Ranpo was known to admire Edgar Allan Poe, a famous Western mystery writer. In fact, his pen name was a spin of Edgar’s name. Other writers who inspired him were Japanese mystery writer Ruiko Kuroiwa and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He was such a fan of Sir Doyle’s works that Ranpo tried to translate said works into Japanese when Ranpo was just a student at Waseda University.

Hailing from Nabari, Ranpo’s hometown is in Mie Prefecture. At the time, his grandfather was a samurai who served the Tsu clan. Later on, Ranpo’s family moved to a place that is now known as Kameyama, still located in Mie Prefecture. At the age of 2, his family moved again to Nagoya. Beginning in the year 1912, Ranpo enrolled at Waseda University to study economics.

Four years later, Ranpo graduated university with a degree in economics in the year 1916. After that, he got into a series of random jobs just to gain experience and earn money. These jobs included drawing cartoons for magazine publications, manning a used bookstore, editing newspapers, and selling soba noodles along the streets.

After so many odd jobs, Ranpo was finally able to make his literary debut in the year 1923. His first mystery story that appeared in the literary scene was entitled “Ni-sen doka,” which translated to “The Two-Sen Copper Coin.” It was printed in Shin Seinen, a well-known magazine at the time that catered to an adolescent audience. The magazine was known to have published stories by Western authors such as Edgar Allan Poe, G. K. Chesterton, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Ranpo’s work was actually the first mystery fiction written by a Japanese that the magazine published.

It was the beginning of Ranpo’s career as a writer. After some time, Ranpo became a writing regular for some famous public journals of popular literature. His voice in the Japanese mystery fiction circle became loud and clear. With his several stories being published left and right, a character that became a regular feature was Kogoro Akechi. The detective hero character first appeared in “The Case of the Murder on D. Hill.”

In these stories, it was quite common for Akechi to be fighting against a criminal character known as Kaijin ni-ju Menso, which can be translated to “the Fiend with Twenty Faces.” As his name suggested, this antagonist had the ability to change his appearance, which proved to be useful as he moved throughout the city. Some of these novels were actually adapted into films later on. The introduction of Akechi’s sidekick, Kobayashi Yoshio, was made in the novel in the year 1930.

His Life During and After the Second World War

During the lifetime of Ranpo, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Second Sino-Japanese War occurred in the year 1937. Just two years after these horrible events, Ranpo received orders from government censors to stop publishing his story entitled “Imo Mushi,” which translated to “The Caterpillar.” The story was published before without any problem. However, the government censors wanted the story to be removed from a collection of Ranpo’s works that were being reprinted by Shun’yodo, the publisher.

The story revolved around a man who was a veteran coming home from war. He became a quadriplegic due to the battle he was in and became disfigured. As a result, his life became similar to that of a caterpillar wherein he was not able to speak, move, or live alone. The story was banned by censors thinking that it was not reflective of the current war effort at the time.

The drop of this story affected Ranpo financially. He was dependent on the royalties from reprints of his works for income. The short story served as an inspiration to Koji Wakamatsu, a director of the film “Caterpillar.” The movie was even nominated for the Golden Bear at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival.

During the war between Japan and the United States of America, Ranpo was actively participating in his neighborhood organization to boost the morale of the people. Being a patriot, he wrote stories that revolved around young detectives that many people believed to be in line with the war effort. However, he wrote most of these stories under different guises instead of using his own pen name.

Following the end of the war, Ranpo continued to dedicate his time and effort to promoting mystery fiction. He wanted readers to understand the history of the genre as well as to encourage new writers to try their hand at mystery fiction stories. A new journal known as Hoseki, which can be translated to “Jewels,” gained his support in the year 1946.

The said journal was dedicated to mystery fiction. A year later, Ranpo also founded the Tantei sakka kurabu, which can be translated to “Detective Author’s Club.” The club was renamed to Nihon Suiri Sakka Kyokai, which can be translated to “Mystery Writers of Japan,” in the year 1963.

Ranpo also tried his hand in writing about the history of mystery fiction not just in Japan but also in the US as well as in Europe. Written in essays, several of these were published in the form of books. Most of his works after the war revolved around Kogoro Akechi and the Boy Detectives Club. These novels catered to juvenile readers.

Also following the war, most of Ranpo’s books were adapted into films. Even after he passed away, some of his works still continued to be made into movies. Sadly, Ranpo suffered from various illnesses. These included atherosclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Eventually, Ranpo passed away in his home in the year 1965 due to a cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried at the Tama Cemetery located in Fuchu, which is near Tokyo.

A Japanese literary award was also named after Ranpo called the Edogawa Ranpo Prize. The Mystery Writers of Japan has presented this award annually since the year 1955. The winner of the prize gets to take home 10 million yen as well as publication rights by Kodansha.

Edogawa Ranpo’s Works in Anime and Manga

By UnknownUnknown author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By UnknownUnknown author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Edogawa Ranpo’s works had been adapted into manga and anime due to its immense popularity. Also, some of his works served as an inspiration to create new animations. An example of this would be Chiko: Heiress of the Phantom Thief. This anime series was a spin taken from Ranpo’s “The Fiend with Twenty Faces.” In the series, Ranpo was re-casted as an anti-hero father figure.

For a retelling of a story written by Ranpo, one may look into the anime series entitled “Trickster.” Incorporating a futuristic theme, it tells the story of The Boys Detective Club. Specifically, the series revolves around the sidekick of Akechi and his friends. Under the leadership of Akechi, they try to solve mysteries together. The Boys Detective Club can be compared to either Nancy Drew or The Hardy Boys.

Because most of Ranpo’s works incorporated supernatural themes, the same also went with the anime series. The boy detective in the series named Kobayashi is an immortal being who can survive several deadly situations. However, despite his immortality, he actually hates living.

Another anime series that can be linked to Ranpo is one entitled “Ranpo Kitan: Game of Laplace.” The series is basically an amalgam of all the most popular works written by Ranpo. It can also be considered as another spin on the Boys Detective Club. In this series, Kobayashi was re-casted as a genius who was only able to sneak his way into the detective work of Akechi. What makes this anime series unique is that it takes the original stories made by Ranpo to an extreme level.

As for a manga, one can check out a series entitled “Imo-mushi.” This manga series was based on the work of the same title written by Ranpo. The manga was created by Suehiro Maruo. A fan of Ranpo’s works, Maruo uses the most popular stories made by Ranpo to make adaptations. An example of this is “The Caterpillar.” The story of “Imo-mushi” appears to be a perfect fit for the unique art style of Maruo.

Other Books and Quotes by Edogawa Ranpo

By All credit to his author. (UnknownUnknown source) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By All credit to his author. (UnknownUnknown source) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Aside from the stories involving Akechi, Ranpo also created several other stories throughout his lifetime. These stories mainly focused on crimes and mysteries and how to solve them. Some of these stories are actually considered classics of Japanese popular literature today. An example of this is entitled “D-zaka no satsujin jiken,” which can be translated to “The Case of the Murder on D. Hill.” Published in January of the year 1925, the story revolves around a woman who was murdered while in a sadomasochistic extramarital affair.

Another work made by Ranpo was entitled “Yane-ura no Sanposha,” which can be translated to “The Stalker in the Attic.” Published in August of the same year, the story revolves around a man who murders his neighbor while inside a boarding house in Tokyo. He committed the crime by dropping poison through a hole that can be found on the floor of the attic of the house. The poison dropped into the mouth of his victim, which caused the latter’s death.

Just two months after that, Ranpo published another story entitled “Ningen Isu,” which can be translated to “The Human Chair.” Appearing in October of the year 1925, the story revolves around a man who constantly keeps himself hidden in a chair. The purpose of this is to let him feel the bodies sitting on top of him. Several optical devices were also often used in stories made by Edogawa. An example of this would be “The Hell of Mirrors.”

Of course, the most popular work of Ranpo still remains to be his creation Kogoro Akechi. This long-lived character is like a Japanese version of Sherlock Holmes. Akechi first appeared in “The Case of the Murder on D. Hill.” Ranpo did not steer clear from supernatural themes; in fact, he incorporated many of them in his stories. An example of this would be his novel entitled “Kyuketsuki,” which can be translated to “Vampire.” As the name suggests, the story involves vampires.

Akechi’s sidekick was only created and introduced by Ranpo in order for his works to also cater to younger readers. What skyrocketed Akechi’s popularity was the Shonen Tanteidan, which can be translated to the “Boy Detectives Club.” This series was so popular that it spanned decades and outshone even Akechi himself. Until today, this series can still connect to modern Japanese audiences.

Ranpo had created numerous stories throughout his life. These stories did not only challenge the imagination of the younger generation but also served as an inspiration to other artists and creators. Having spearheaded the mystery fiction genre in Japan, Ranpo played a significant role in developing this specific genre in the Japanese literary scene. Thanks to Edogawa Ranpo, new writers were encouraged to try their hand at mystery fiction and create new worlds that would challenge the minds and inspire the hearts of the Japanese people.