How Hot is That Pepper? How Scientists Measure Spiciness

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/FoodandThink-Chili-Peppers-631.jpg)

In 2007, the Naga Bhut Joloki or “Ghost chile” was named the hottest pepper on earth. Then in 2010 the Naga Viper stole the title. And in 2012 the Trinidad Scorpion Moruga Blend moved into the lead. And for good reason.

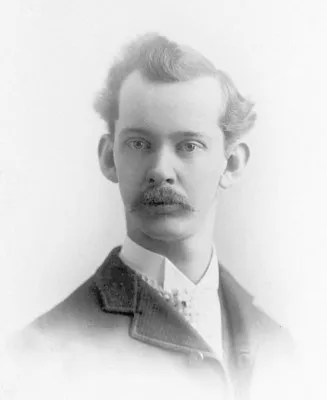

The Scorpion ranks at round 2 million heat units on the Scoville scale. (For comparison, tabasco sauce has 2,500–5,000 Scoville heat units or SHU.) What exactly does that mean? When the scale was invented in 1912 by pharmacist Wilbur Scoville in search of a heat-producing ointment, it was based on human taste buds. The idea was to dilute an alcohol-based extract made with the given pepper until it no longer tasted hot to a group of taste testers. The degree of dilution translates to the SHU. In other words, according to the Scoville scale, you would need as many as 5,000 cups of water to dilute 1 cup of tobacco sauce enough to no longer taste the heat.

And while the Scoville scale is still widely used, says Dr. Paul Bosland, professor of horticulture at New Mexico State University and author or several books on chile peppers, it no longer relies on the fallible human taste bud.

“It’s easy to get what’s called taster’s fatigue,” says Bosland. “Pretty soon your receptors are worn out or overused, and you can’t taste anymore. So over the years, we’ve devised a system where we used what’s called high performance liquid chromatography.”

That’s a fancy way of saying that scientists are now able to determine how many parts per million of heat-causing alkaloids are present in a given chile pepper. The same scientists have also figured out that if they multiply that number by 16, they’ll arrive at the pepper’s Scoville rating (or “close enough for the industry,” says Bosland).

And, let’s face it, who would want to be the one to taste test a pepper named after a viper or a scorpion? Or maybe the better question is what sane person would? The BBC recently reported on the first man to finish an entire portion of a curry made with ghost chiles, called “The Widower,” and he suffered actual hallucinations due to the heat. Bosland told the AP in 2007 he thought the ghost chile had been given it’s name “because the chili is so hot, you give up the ghost when you eat it.” How’s that for inviting?

Indeed, the capsaicin, the spicy chemical compound found in chiles demands the diner’s attention much like actual heat heat does. And it turns out there’s science behind that similarity. “The same receptor that says ‘hot coffee’ to your brain is telling you ‘hot chile peppers,’” says Bosland.

And what about the rumor that very hot peppers have the potential to damage our taste buds? Not true. Bosland says we should think of chile heat like we do the taste of salt; easy to overdo in the moment, but not damaging to your mouth over the long term. Even the hottest habanero (100,000–350,000 on the Scoville scale), which can stay on your palate for hours — if not days – won’t wear out your tender buds.

Bosland and his colleagues have broken the heat profile of chile peppers into five distinctly different characteristics. 1) how hot it is, 2) how fast the heat comes on, 3) whether it linger or dissipates quickly, 4) where you sense the heat – on the tip of tongue, at the back of throat, etc., and 5) whether the heat registers as “flat” or “sharp.”

This last characteristic is fascinating for what it says about cultural chile pepper preferences (say that five times fast). Apparently those raised in Asian cultures — where chile heat has been considered one of the six core tastes for thousands of years — prefer sharp heat that feels like pinpricks but dissipates quickly. Most Americans, on the other hand, like a flat, sustained heat that feels almost like it’s been painted on with a brush.

The Chile Pepper Institute, which is affiliated with New Mexico State University, sells a nifty chile tasting wheel, which describes the heat and flavor profiles of many different chiles and offers advise on how to cook them.

Eating chiles is a little like tasting wine, says Bosland. “When you first drink wine, all you notice is the alcohol. Then you can tell red from white, and soon you can taste the difference between the varietals. Eventually you can tell what region the wine comes from. That’s how it is with chile peppers too. At first all you taste is heat, but soon you’re be able to tell which heat sensations you like best.”